November 27, 2025

November 27, 2025

Average Employee Turnover Rate by Industry

Published by:

David Whitfield

,

CEO & Co-Founder

,

HR DataHub

Reviewed by:

Alexa Grellet

,

COO & Co-Founder

,

HR DataHub

10

MIN READ time

If you’re reading this, chances are you’ve just looked at your latest turnover report and thought: “Is this normal for our industry – or do we have a problem?”

It’s a fair question. CIPD’s latest analysis of the UK labour market suggests around a third of employees either move employer or leave work each year, with churn ranging from roughly 25% in public administration and defence to over 50% in hospitality, so the same number can mean very different things depending on where you sit.

In this article, I’ll answer the following questions:

- What is the average employee turnover rate in the UK?

- What are the average employee/staff turnover rates by industry?

- Which industries have the highest turnover?

To do that, I’ll lean primarily on CIPD’s employee turnover benchmarks, and complement them with sector-specific UK data from additional sources. That mix should give you a grounded view of how your organisation stacks up.

And if your headline number looks scary, don’t panic. I’ll walk you through how to interpret it for your sector and what to do next if your turnover is higher (or lower) than the industry benchmark.

What do we mean by employee turnover?

When I talk about employee turnover in this article, I’m using this basic definition: the proportion of your workforce who leave over a given period, usually a 12-month window.

In simple terms, it’s your total number of leavers divided by your average headcount, expressed as a percentage.

Turnover rate = (Total leavers ÷ Average number employed) × 100

Your average headcount is typically the mean of your employee numbers at the start and end of the period.

It can be helpful to separate these two types of employee turnover:

- Total turnover – all leavers (resignations, retirements, redundancies and dismissals)

- Voluntary turnover – only people who resign

Many HR leaders I speak to are really worried about that voluntary element, because it’s where you have the most control and where you risk losing key employees.

Throughout this guide, I’ll flag where sources include redundancies or focus on voluntary leavers only, because that makes a big difference to how your turnover rates compare with industry benchmarks.

The average employee turnover rate in the UK

CIPD’s latest analysis of the UK labour market, based on the Annual Population Survey, puts the average employee turnover rate at around 34% between January 2022 and December 2023.

Of that, roughly 27.4% of employees move to another employer, while around 6.6% are no longer in work a year later, for example, because they’ve gone into study, retired, or are out of the labour market due to long-term sickness or caring responsibilities.

That doesn’t mean a third of the workforce is leaving every year. CIPD’s longitudinal data shows that most UK employees stay with the same employer, with typical tenure often sitting in the two-to-five-year range, depending on the industry. After the disruption of the pandemic and the great resignation, churn has largely stabilised, but it remains material in many sectors.

Employee turnover rates by industry in the UK

A single national average employee turnover tells you very little. Whereas, industry benchmarks can show you whether your staff turnover rate is in line with the market or a genuine cause for concern.

How CIPD benchmarks turnover by industry

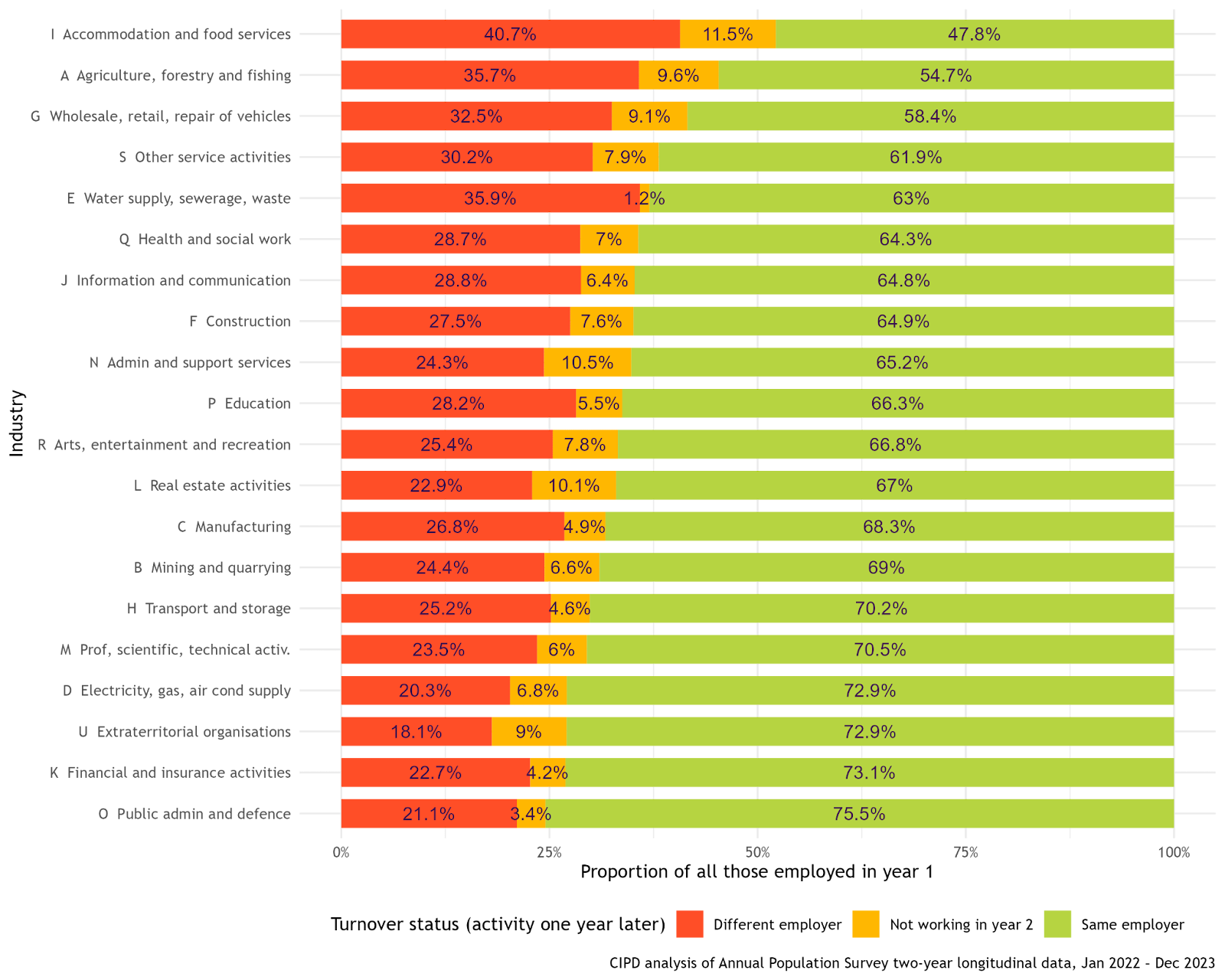

We’re drawing on CIPD’s latest analysis, which uses the Annual Population Survey (APS), a large ONS household survey that tracks what people are doing at one point in time and again a year later. That longitudinal view makes it possible to see how often people move between sectors.

The figures we’ll use here cover January 2022 to December 2023, which is the latest full APS period available. They’re nationally representative averages across broad sectors. Individual employers and sub-sectors will sit above or below these lines.

UK employee turnover rates by industry

Source: CIPD, Benchmarking employee turnover: What are the latest trends and insights?, June 2024

Accomodation and food services - 52.2%

Agriculture, forestry and fishing - 45.3%

Wholesale, retail and repair of vehicles - 41.6%

Other service activities - 38.1%

Water supply, sewage and waste - 37.1%

Health and social work - 35.7%

Information and communication - 35.2%

Construction - 35.1%

Admin and support services - 34.8%

Education - 33.7%

Arts, entertainment and recreation - 33.2%

Real estate activities - 33%

Manufacturing - 31.7%

Mining and quarrying - 31%

Transport and storage - 29.8%

Professional, scientific and technical activities - 29.5%

Electricity, gas and air conditioning supply - 27.1%

Extraterritorial organisations - 27.1%

Financial and insurance activities - 26.9%

Public admin and defence - 24.5%

These industry averages are your starting point for turnover benchmarks by industry. If you’re running a hotel, restaurant or leisure site, you’d expect a much higher “natural” churn than, say, a local authority or specialist manufacturer. The question then becomes: are you broadly in line with your sector, significantly above it, or unusually low?

High-turnover industry: hospitality, catering and leisure

Hospitality (accommodation and food services) sits at the top of the high-turnover industries list at around 52% churn, far above the UK average of 34%.

More recent data from RotaCloud, reported on by Catering Scotland, tells a similar story for 2024. Looking across more than 4,000 accounts, they found a staff turnover rate of 38.7% in hospitality and catering, the highest of any industry group in their dataset. Within that, turnover hits 47% in bars and clubs, 43.2% in quick-service restaurants, 39.1% in restaurants and cafés, 34% in catering and events, and 30% in delis and bakeries.

Across hospitality, the pattern is familiar: a high proportion of lower-paid, shift-based and often high-stress roles, younger workforces, and intense demand pressures. CIPD also points out that, where roles are often lower paid and skills are more transferable, the cost of replacing leavers is lower, so a higher churn rate is less damaging than it would be in, say, an engineering firm or professional practice.

This is why it’s so important to interpret “high” or “low” against the right industry benchmarks, not against the UK average alone.

Lower-turnover industries: manufacturing and some public services

At the other end of the spectrum, manufacturing currently shows much lower turnover rates. Make UK’s latest Labour Turnover report finds that overall turnover in manufacturing was 10.85% in 2024, down from 16.12% in 2023 and 20.75% in 2022 – the lowest level in at least a decade. Turnover excluding redundancies has fallen even further, to 6.24%, and retirement is now the main reason for people leaving, reflecting an ageing workforce.

In public administration and defence, CIPD’s benchmarks show attrition at around 25%, substantially below the UK average.

Certain demographics within education tend to sit toward the lower end: DfE’s latest School Workforce in England statistics show that around nine in ten early-career teachers remain in state-funded schools one year after qualification, implying churn of roughly 10% in that group specifically, despite CIPD’s data suggesting that the education employee turnover rate sits at around 33% overall.

Adult social care: a sector in transition

Adult social care is a good example of why I’m cautious about labelling sectors as simply “high” or “low” turnover. The latest State of the Adult Social Care Sector and Workforce in England, reported on by Care Management Matters, shows that 24.2% of people working in care left their jobs in 2023/24, down from 29.1% the previous year, a notably positive shift after years of intense workforce pressure.

At the same time, it points out that, while vacancy and turnover rates are falling and the workforce has grown, the sector still faces long-term recruitment and retention challenges.

For HR leaders in social care, that means viewing a roughly one-in-four turnover rate not just against the UK average, but in the context of a system that is gradually stabilising yet still under structural strain.

Context is everything

You can absolutely see from all of this that context is everything. These sectors illustrate that average turnover rate by industry ranges widely – which is why a single “good” or “bad” number simply doesn’t exist.

CIPD’s analysis gives us a robust, nationally representative view, but every dataset has its limits – different definitions of turnover, varying coverage of sectors and job types, and time lags.

On top of that, the reality is that many organisations still don’t treat turnover as a core metric. CIPD’s latest Resourcing and Talent Planning report finds that only 31% of organisations who know their turnover figures actually calculate the cost of labour turnover. And at FTSE 100 level, CIPD and Railpen’s Future of Workforce Reporting shows that just 38% of companies disclose their turnover rate in annual reports.

So while these benchmarks are the best we have, they’re still averages sitting on top of incomplete reporting.

How to spot and fix high-turnover areas in your organisation

Because external benchmarks are imperfect, I always encourage HR teams to start with their own data. Once you’ve calculated your overall employee turnover rate, break it down into meaningful slices, such as:

- Business unit or function

- Role or job family

- Location or site

- Contract type

- Seniority

This will help you quickly reveal high-turnover hotspots to focus on.

From there, the question becomes why are those areas seeing high turnover?

You want to understand the core drivers of high turnover in this segment:

Is it low pay? Poor management? Limited progress? High stress?

It’s a good idea to run exit interviews and stay interviews, as well as engagement surveys to help surface familiar themes. You can then understand how remaining employees feel in their roles.

If pay is a significant issue identified as a driver for high churn, then you can use our salary benchmarking tool to confirm whether pay is genuinely out of line compared to the market.

On top of that, it’s important to assess development opportunities and improvements to leadership and working practices that will help to create an environment where people feel valued and want to stay.

I cover this in more detail in my article on employee retention strategies. I also touch specifically on how to retain staff in retail and hospitality.

FAQs

Which industry has the highest staff turnover?

Across the UK, hospitality (specifically accommodation and food services) consistently sits at the top of the table for staff turnover. CIPD’s places hospitality at around 52% attrition, compared with a UK average of 34%. More granular 2024 data from RotaCloud shows a 38.7% turnover rate in hospitality and catering, rising to 47% in bars and clubs and over 43% in quick-service restaurants. In other words, if you’re running a bar, restaurant or venue, very high churn is unfortunately “normal” for the industry.

Is 20% staff turnover high?

The honest answer is: it depends where you sit. If you’re in a lower-turnover sector, for example, manufacturing or parts of the public sector, a 20% turnover rate may be a warning sign. Make UK’s latest figures show overall manufacturing turnover at around 10–11%, and closer to 6% when you exclude redundancies, so 20% would mean you’re losing people at roughly double the sector norm.

In schools and some early-career teaching roles, implied churn is also closer to 10% than 20%. By contrast, if you’re running a bar, café or quick-service outlet, 20% would actually be better than the averages we see in the hospitality data.

Is 30% staff turnover bad?

At 30%, you’re just under the UK average of around 34%, so I’d treat it as a “pay attention” zone rather than an automatic crisis.

In low-churn sectors like manufacturing, where the typical organisation sits in the low-teens or single digits, 30% would be very high and worth urgent investigation. In adult social care or early years, 30% would be on the high side but not unheard of, given historic recruitment and retention pressures and the fact that some parts of those systems are still stabilising.

In hospitality, though, 30% would actually be relatively healthy compared with industry averages in the mid-30s to mid-40s. For a bar or quick-service venue, it would suggest you’re doing a better-than-average job of retaining people,

Understand your own turnover hotspots and why people are leaving

Once you’ve got a picture of your own retention issues, you can make deliberate choices about where to invest: pay, development, leadership, culture, or all of the above.

The biggest lever in most organisations is pay: are you genuinely competitive for the roles and locations where churn is highest? HR Datahub gives you clear, market-driven evidence on pay, so you can close gaps, make confident reward decisions and reduce the risk of people leaving simply because they can earn more elsewhere.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

.jpg)